Q&A with Saskia Olde Wolbers

http://blogs.artinfo.com/modernartnotes/2008/02/qa-with-saskia-olde-wolbers/

Comments Off

Bookmark and Share

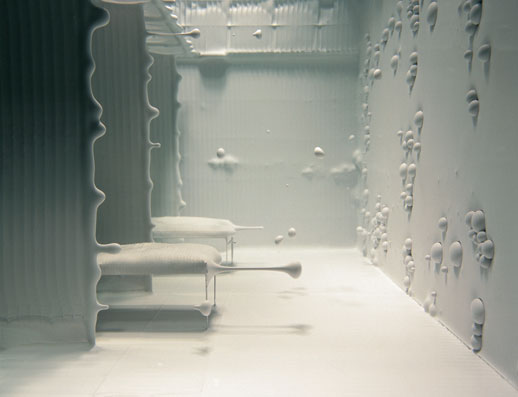

PlaceboOldeWolbers.jpgThe first time I saw a Saskia Olde Wolbers was at the Hammer in 2003, where Placebo (2002) was showing in a Hammer ‘Projects’ group show. I was hooked from the first moment: the lush, rich, oozing visuals were other-worldly. It took me a minute to hear the voiceover, and another minute to teach myself how to divide my attention equally between the video and the narrative — and by then the six-minute video was up. I figured out how long it would be before Placebo (left) played again, went upstairs to see something else at the Hammer, and returned in time for Placebo to restart. I think I did that one more time that day, and several times over the course of that visit to Los Angeles.

Few video pieces have stuck in my mind like Placebo. It’s catchy like Pipilotti Rist’s Ever is Over All, it’s visually sumptuous in the same way a Shirin Neshat is, and it’s slow like a good Bill Viola. But while each of those artists shows us a narrative, Olde Wolbers writes us one. Her visuals are super, but it’s her cleverness as a writer that keeps me going back a third or fourth or fifth time.

Placebo opens with a line that could have started a classic novel or the best vintage bit of Hollywood noir: “Here I am, lying next to my lover Jean, in intensive care, slipping in and out of consciousness in shifts. Life slowly dripping out of us…” So too Trailer (2005), which is on view now at the Hirshhorn as part of Kerry Brougher and Kelly Gordon’s The Cinema Effect show: “Somewhere in the vast Amazonian forest, among plants whose indigenous, Spanish and Latin names compete with one another outside of their awareness, three species stood out self-consciously. There was the ancient red bark tree by the name of Ring Kittle. And in his shady undergrowth the Elmore Vella, a species of flytrap, used to go quietly about her deadly business.”

For the next 10 minutes Trailer’s narrative wanders away, folds over itself, slips along, and then doubles back in a too-real-to-be-true self-referential loop. Olde Wolbers’ stories are like ice crystals: They’re beautiful and complicated, and you have to examine them carefully to fully appreciate them. Then, just as you begin to figure them out, they melt and vanish. I’ll have plenty of opportunities to ’solve’ Trailer: The Hirshhorn has acquired the piece for its collection.

Olde Wolbers, who is Dutch, lives in London and has never had a solo show in the U.S. She visited the Hirshhorn for the opening of The Cinema Effect and I talked with her about Saskia Olde Wolbers, the writer. Come back for part two tomorrow.

OldeWolbersTrailerTheater.jpgMAN: Are you a writer?

Saskia Olde Wolbers: No. But I guess fiction is my main source of inspiration I’m constantly reading and writing things down, but you know I think writing is difficult. When I’m making actual work, I guess sort of it is ninety percent of it is making, making sets in the studio. In the studio I listen to a lot of novels on tape, so I am constantly engaged in ways of narrating. Even if I’m socializing, I’m looking for stories, so I’m definitely listening for stories. That’s sort of an interest of mine, the way writers sort of filter experience in a distant way: They see the actual story as well as the emotional experience.

MAN: So when you’re working on a piece, do you start with writing, with narrative, or do you start with visuals?

SOW: I usually start a piece with a very thin premise. For instance with Trailer (above right) I stumbled upon a documentary about Judy Lewis, who was the daughter of Clark Gable and Loretta Young, and by the time she found out Clark Gable was her dad she could only see him in his roles. So I started with that distance, how film creates something but it’s not really personal per se.

I had just been in Los Angeles, so I started working on the idea of the cinema as a building, and the jungle as a sort of place for fiction. So I had different strands, but I never have one or the other finished first.

MAN: So you don’t sit down and write out the whole story in one or two sittings?

SOW: No. I do the writing only in pieces. I have a notebook, so I make notes and then I put it into a PC and I end up with lots and lots of unrelated material. I add things I find along the way and then I edit it down.

MAN: Do you outline or go with flow?

SOW: Towards the end, when the visuals are almost done and the story has to come together, I do guide it a bit. But when editing I lay the narrative/voice over down first and then I can slot the visuals into it.

MAN: You’ve mentioned fiction a few times. Tell me what you read.

SOW: There are definitely some particular writers. There is a sort of particular feel I guess to what stories I like. I wouldn’t read just anything… What did I just read? Oh, I just read Dave Eggers’ What is the What and I really liked that. It was great company. [Olde Wolbers also emailed me her reading-plus list. Click below to see it.]

Part two is here.

Salman Rushdie, Midnight’s Children, 1981

Oliver Sacks, An Anthropologist on Mars

Ryszard Kapuscinski, The Shadow of the Sun

Hearts of Darkness; a filmmaker’s apocalypse, 95 min colour, USA, 1991

Bahr Fax, et al. (documentary about the making of Francis Ford Coppola’s film Apocalypse Now)

Les Blank, Burden of Dreams, 95 min colour, USA, 1982 ( documentary about the making of Werner Herzog’s film Fitzcarraldo)

Alejo Carpentier, The Lost Steps, 1953

Werner Herzog, Aguirre; The wrath of God, 90 min, colour, Germany

Haruki Murakami, The Wind-up Bird Chronicle, 1999

Chris Marker, Sans Soleil USA:100 min, 1983

Lauren Slater, Opening Skinners Box; great psychological experiments of the 20th century

Ian McEwan, Enduring Love, 1997

Robert Altman, Nashville, 160 min, colour, USA, 1975

Jim Krusoe, Bloodlake and other stories, 1997, Iceland, 2002

Lars von Trier, The Kingdom, 279 min, colour, Denmark, 1994

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Half of a Yellow Sun

Tobias Wendl, Wicked Villagers and the Mysteries of Reproduction. An Exploration of Horror Movies from Ghana and Nigeria. In: Rose-Marie Beck and Frank Wittmann (Eds.), African Media Cultures. Transdisciplinary Perspectives. Köln: Köppe, p. 263-285.

Black Sun, Gary Tarn, 2005, 75mins

Science Is Fiction/The Sounds Of Science, 1927

The films of Jean Painleve

The films of Oskar Fischinger

Amos Tutuola, The Palm-Wine Drinkard, 1946

The private life of plants, David Attenborough, 1995, 50 min

Michel Tournier, Gemini

Mark Hudson, Our Grandmother’s Drums , 1991

Jonathan Safran Foer, Everything is Illuminated

Chinua Achebe, Things Fall Apart, 1958

David Mitchell, Cloud Atlas

Zadie Smith, White Teeth

Decasia; the state of decay, Bill Morrison (2002) 67 min

Paul Theroux, Dark Star Safari

Ben Okri, The Famished Road

Ousmane Sembène, Xala

Susan Faludi, Stiffed: The Betrayal of the American Man

* Home

* Archive

* Contact

Video: http://www.dailymotion.com/video/x7lta_the-falling-eye

Saskia Olde Wolbers

Artvehicle 25/Review

http://www.artvehicle.com/events/72

6th October 2007 — 11th November 2007

In the downstairs gallery space of Maureen Paley a sequence of fifty snapshots depicts various aspects of life somewhere in Africa. Images of tired buildings, abandoned or not yet completed, sit alongside pictures of children playing in the street. These could almost be the photographs of a naive traveller charting his first experience of backpacking, but the focus on unusual modernist architecture and abstract industrial forms takes them somewhere else. In one, a truck lies upturned by the side of the road, its cargo of timber spilt. In another, two men stand in the dark, one holding a rabbit, the other a knife. What begins as a seemingly banal succession of images develops into an unusual and compelling narrative.

This sequence is a document of a journey made by Saskia Olde Wolbers and is presented as source material for the video piece Deadline which is projected in the space upstairs. The voice of a Gambian woman, Salingding, narrates the film and tells the remarkable story of her family history and of her own sixteen-month journey across 3000 miles of west Africa. In 1960, her grandfather's two wives gave birth to two boys in adjacent rooms, on the same hour of the same day. They are described as twins who had the 'luxury of having grown in their mothers alone'. One of these boys, who would become Salingding's father, was deemed to be the younger by virtue of the fact that he was thought to be a week early, and so these two lives had their fates sealed almost at random.

The story runs almost in the form of a poem and the narrator's voice is accompanied by distant African drums. It seems appropriate to describe the sound before the visual because it is such an extraordinary tale and it is stunningly rendered. Indeed the aural is so powerful that for much of the film it dominates what we see on screen. This is not to take away from the imagery, but the narrative is so rich that at times the visuals struggle to compete, or there seems to be an imbalance of some kind between the two. Like much of Olde Wolbers's work the content is neither wholly based on fact nor purely imagined. She constructed Salingding's narrative from an amalgamation of stories from several different individuals that she met in a Gambian fishing village; a mixture of local folklore and actual histories.

The imagery itself alludes to various aspects of the monologue and is typical of Olde Wolbers's previous work in its abstraction of commonplace objects. She creates strange and unfamiliar landscapes which are imbued with a kind of hypnotic quality through her use of slow, but often very extended, camera movements. There are five or six principal visual themes running through the piece. One depicts snake-like forms with scales coloured like the flags of African nations. This references the 'Ninki Nanka', a python which has the head of a termite and carries a small diamond on its cranium. Another depicts a glass rabbit dripping blood, upwards, from its head. Slowly the relationship to the photographs on the ground floor of the gallery becomes apparent. The woman describes how her brother hit a rabbit while driving. 'He got out of the cab and slit its throat, announcing breakfast as he threw its limp body in the back of the van.'

Towards the end of the film Salingding asks 'do we all have journeys mapped out in our central nervous systems like migrating birds? It seems the only way to account for our insane restlessness' The idea of the journey has always captivated the human imagination. There is a certain romanticism attached to the notion of the traveller as someone liberated from the banality of the everyday. Conversely, people's reasons for moving from one place to another can also be desperate and even essential to survival. Olde Wolbers's film charts an economic migration of a family, a story that falls very firmly within the scope of the latter of those two categories. It offers a bleak portrayal of how fragile the hopes of those who 'desire to travel away from the everyday squalor' can be. Of how corruption, or crime or governments or any number of factors can stand between people and their dreams of a better life for themselves and their families.

No comments:

Post a Comment