Slide show:

news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/in_pictures/8305619.stm

Martin Firrell

Keith Tyson

.jpg)

Ed Ruscha

news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/entertainment/arts_and_culture/8305617.stm

news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/entertainment/arts_and_culture/8305617.stmTracy Emin

By Alex Hudson

BBC News

"We navigate our whole lives using words. Change and improve the words and I believe we can change and improve life."

Public artist and campaigner Martin Firrell has some big ideas about the use of words in art - both in scope and in scale.

He has emblazoned his work on St Paul's Cathedral, across the exteriors of both the Royal Opera House and the National Gallery, on each occasion the first artist to do so.

Originally trained as an advertising copywriter, his next project Complete Hero will involve a projection on to London's Guards Chapel from next month.

He has enlisted the help of members of the Army along with scientists, philosophers, thinkers and writers to question the modern idea of heroism.

But his project is just the latest example of the use of text in art.

Different picture

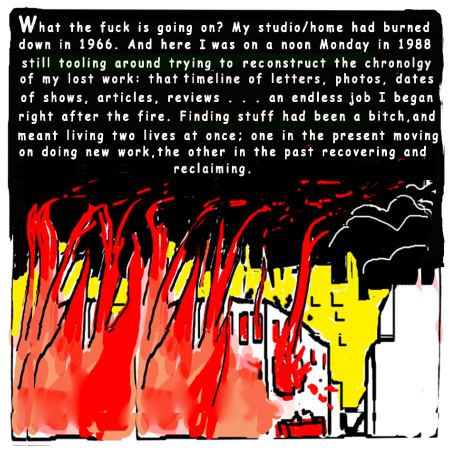

"When you look back in history you will see artists have forever used words in paintings," said the artist Ed Ruscha.

"There was a quiet time and come the 20th Century there was a different picture. There was a time in the 1930s, 40s, 50s where artists were producing abstract pictures that were off on their own.

"And I think the so-called Pop artists who emerged in the 60s were involved in something that was inevitable."

The Pop Art movement is widely believed to have come as both a reaction against abstract expressionism and a commentary on a new, commercial world.

Andy Warhol was one such artist who notably borrowed heavily from commercial graphic design.

"Some of the critics were so stuffy you couldn't believe their reluctance to accept anything new. Back then, it really was the dark ages," said Ruscha.

This movement reinvigorated the desire for text in art - paving the way for a whole new generation of graphically and media-aware artists.

Currently there is an abundance of artists showing their work.

In London alone, at least four separate exhibitions are featuring the work of text pioneers.

You can even sit in a gallery and read stories written on the walls.

But why would artists turn so quickly towards a form that appears so devoid of "art" in its most traditional sense?

John Baldessari first exhibited his work in the 1960s and has used words throughout his career.

"My ambience was first and second generation abstract-expressionism and I really got tired of hearing the complaint 'my kid can do that' so I said 'what would happen if you really spoke your public's language?'"

But the question remains on many sceptics' lips - is it art?

“ It is an artist's view of what text is, not an English Don's view ”

Keith Tyson, Turner Prize winner

"If I put [words] on canvas... then that's a signal it's art - a very logical way or reasoning," said Baldessari.

"Is it painting? Of course. Paint on canvas, that's a painting isn't it?"

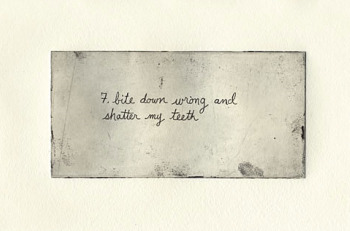

Turner-Prize winner Keith Tyson's work often combines science, nature, art and literature.

In his piece Operator Painting: Large Abstract, the chemical symbol for chlorine sits next to a line of text about a swimming pool attendant, which itself sits above the phrase "children enacting excerpts from The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Big Splashes".

"It is an artist's view of what text is, not an English Don's view", Tyson said.

"It does things that an abstract painting might... or a non-linear novel - it's just a different type of text from the left to right that we're used to."

For others, the imagery created from words can match and even supersede traditional forms of painting.

'A striptease'

Fiona Banner has made a career out of thinking in more varied - and perhaps more complicated - forms than many of her peers.

She was nominated for the Turner Prize in the same year as Tyson, creating a show which described a pornographic film in detail across an entire wall.

Banner has produced works from the gargantuan - a 1,000-page book documenting six Vietnam war films frame-by-frame - to one piece that just consisted of a single, neon full-stop.

The artist has even done work with nudes.

She agreed with the actress Samantha Morton to produce a text portrait of her that Morton would perform the following evening - without ever having read it before.

"It's a striptease in words," Banner said.

"The language that I use is the language that best describes what happens in front of me. If that ends up being seductive language - it is.

"If it ends up feeling distant or objective at times then it is."

As the actress had never read the work before, Banner did not know how the piece would be received.

"The words are not flattering. If my words were a camera, they don't aim to airbrush or flatten, they aim to expose."

'Sub-poetic drivel'

Recently some critics have been using their own words to suggest that text in art could be losing its edge and slowing into decline.

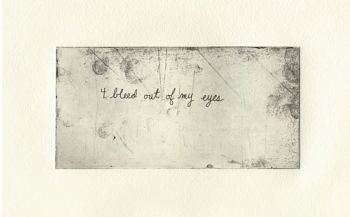

Telegraph art critic Mark Hudson described Tracey Emin's most recent work with text as "sub-poetic drivel" and even described her medium - neon handwriting - as the "most hackneyed medium around".

And the information onslaught and the volume of work available has led John Baldessari to change his view.

"I haven't given up on text... but I would use it very judiciously knowing that we have information overload. It just makes people shut down and not notice it at all.

"The job of an artist is to get people's attention.

"I think I eased off the idea of using text when I thought the battle was won."

Texting Andy Warhol - An Exploration of Writing in Art, presented by the writer Bidisha, is broadcast Thursday 22 October, 1130 BST, on

Story from BBC NEWS:

http://news.bbc.co.uk/go/pr/fr/-/2/hi/entertainment/arts_and_culture/8305617.stm

.jpg)